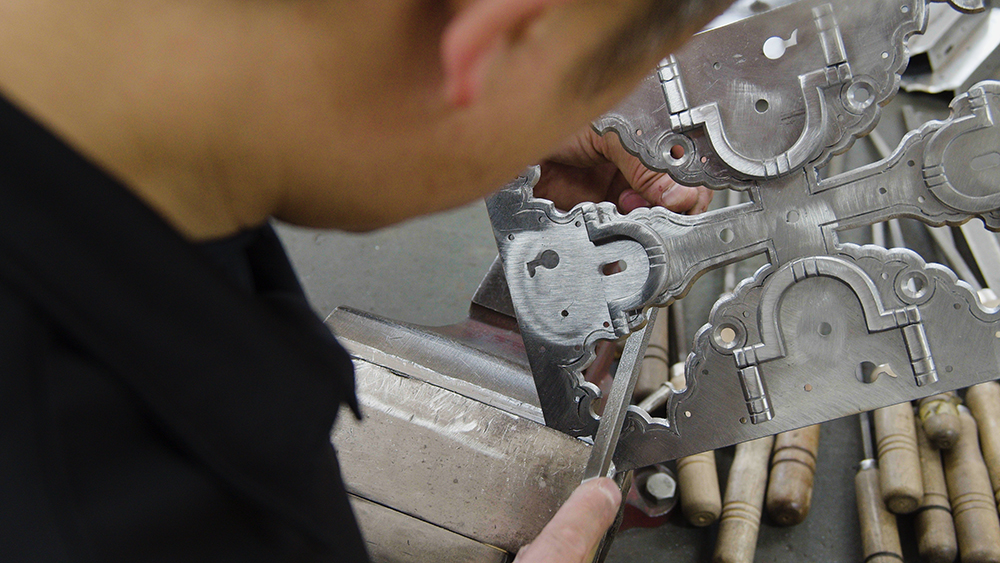

The most artistically valuable ship safety box / chobako cabinet(storage for important documents and banknotes) of all the remaining ones made in the Sakata region of Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. The doors are all covered by conscientious and strong metal fittings dyed to iron black. It has three doors creating chambers for different functions. The first door from the right is for coin storage, the second

door is for a koban (Japanese oval gold coin) storage, and the third door is for a double chamber made of paulownia (hermetic seal and thus waterproof; perfect protection for important documents). There are seven keys with independent functions, On the surface alone,

there are as many as nine keyholes. The keys are so valuable and irreplaceable artworks that no copy works.

Chobako is, in fact, the most important item for shipping agencies (merchant vessel wholesalers and management agencies from the

Edo to the Meiji period). It was even forbidden to offload the cabinet from vessels during the Edo period. Competition among craftsmen

was fierce, which brought about high quality that exceptional cabinets were regarded as the symbol of successful merchants.

Funa-dansu (ship safety box) was used to protect valuables on "kitamaebune (northern-bound ships)" along crucial logistics routes

on the Sea of Japan from the Edo to the Meiji period (1868-1912). The item is practical but gorgeous, like a discernible combination of

security and art. It's heavy, but it can float in the event of any marine accidents. It is, thus, a hermetic seal protection for all

important contents inside. It comes with a complex structure protected by multiple locks and a complicated mechanism that can't be opened easily. After 100 years, the manufacturer took over the traditional wisdom, precisely all materials and structuring techniques, to resemble the safety box from the Edo to the Meiji period.

Art

The most artistically valuable account box

Artist

Solely dedicated to funadansu, the second generation of Takumi Kogei

Hirofumi Murata

After working at an automobile manufacturer for 7 years, he worked as a mechanic.

He became fascinated with funadansu (chests for voyages) after meeting Kenjiro Katsuki, who revived funadansu over 7 years by researching literature and visiting remaining old funadansu across Japan.

He joined Takumi Kogei, a chest and dresser manufacturer founded by Kenjiro Katsuki that builds funadansu with traditional production methods. Since then, he has been focused on crafting funadansu.

He assumed the position of the second head of Takumi Kogei in 2015.

Art Style

Reviving 'funadansu' in the modern era with traditional manufacturing methods

Funa-dansu

Using traditional production methods for creating the base wood material and metal fittings and for applying lacquer, Takumi Kogei manually builds each and every funadansu, which can be described as the roots of Japanese furniture. As such, only about 30 funadansu are built by this chest and dresser manufacturer each year. The second head Hirofumi Murata (metal fittings artisan), who leads the production, and the 5 other artisans of Takumi Kogei, specifically woodworkers and lacquerers, build one funadansu over a period of 4 to 7 months. The production process is divided into several steps, each step performed by a member specializing in that step.

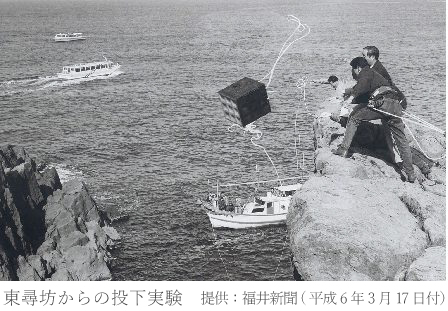

Two conditions are imposed on funadansu that float in the water when a ship sinks. The first one is to be airtight enough to float in the ocean. As valuables almost as important as lives––such as the ship’s travel permit, trade records, invoices, seals, and money––were stored in funadansu, they were thrown in the ocean immediately when an accident occurred during a voyage so that the valuables would not sink together with the ship. For this reason, funadansu had to be highly airtight so that it would float in the ocean without losing the items stored in it. The second condition is that it had to have a complex structure protected with locks so that it could not be opened easily. In case of an accident, funadansu would travel a long distance across the ocean on its own. There was a need to prevent the misuse of the valuables inside the drifted funadansu by a person who found it.

The production of funadansu with traditional methods that meet these conditions has been brought back to life today by Takumi Kogei, currently head by Hirofumi Murata.

Roots

A uniquely Japanese form created by the collective wisdom and skill of craftsmen

Funadansu are elaborate and detailed chests that were loaded on kitamaebune, merchant ships that traversed the Sea of Japan from the middle of Edo period (1603–1868) to the late Meiji period (1868–1912). Called an essential for the merchant ships, funadansu were purchased by numerous sailors.

The development of shipping by kitamaebune originated from the establishment of the Western route that connected Osaka and Hokkaido (formerly Ezochi). A wide range of goods were delivered to various locations in the country by kitamaebune. As there was still a significant time gap in the transmission of information back then, the merchants made huge profits by taking advantage of that time gap in their trading activities.

At the beginning of the history of kitamaebune, many cargo ships of Kono-ura, Echizen and other locations in the Hokuriku region shipped goods of the merchants based in the Omi region. By the late Edo period, ship owners of the Hokuriku region began to transport their own goods for trade, leading to the development of kitamaebune ships as merchant ships.

The prosperity of Kitamaebune trade came to an end in 1885 when the government issued an order banning the production of Japanese style ships (wasen) due to frequent marine accidents involving wasen. While kitamaebune trade continued to decline from thereon, land routes were developed one after another and funadansu gradually became devoid of purpose.

Nevertheless, as funadansu––with a configuration unique to Japan and unparalleled in the world––are extremely durable and highly water-resistant, a number of funadansu from the times of kitamaebune remain today. These antique funadansu, the result of the wisdom and skills of artisans, are stored and/or displayed at museums and other facilities in several locations in Japan.

特集記事一覧

Connecting People and Tradition through Dyeing

Exploring the Charms of Miyazu City, Kyoto Prefecture

A Hidden Gem of Otsuki City: Experience Guide to Enjoy with Mount Fuji

A Heartwarming Journey through a Treasure Trove of Nature and History

Experiencing History and Inherited Memories in Asuka Village

Discover! The Charm of Miki City

The Enchanting City of Morioka

Discovered! Exciting in Tokushima and Naruto City